Foreign investment control in france (FDI Screening)

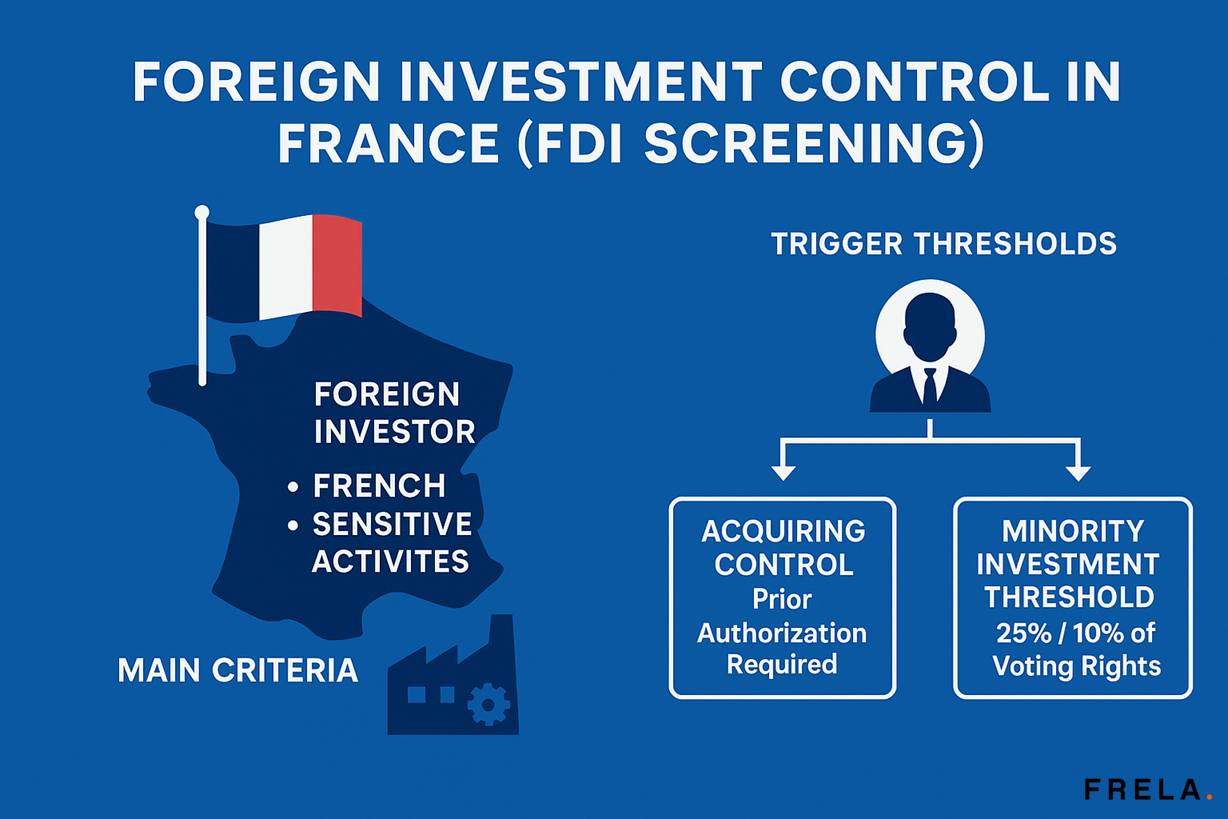

Foreign investors acquiring French companies must consider France’s foreign investment control regime. France operates a mandatory and suspensory FDI screening for certain investments, meaning qualifying deals must be approved by the French Ministry of Economy before closing. This can directly affect transaction timing and deal certainty for a foreign acquirer.

When is FDI Approval Required?

The rules (in the Monetary and Financial Code, Articles L.151-3 and R.151-1 et seq.) set out three main criteria:

- Foreign Investor Criterion: The investor must be “foreign” as defined by law. This includes any non-French individual or entity, or even French entities controlled by non-French interests. Notably, EU/EEA investors are treated more leniently in some respects – for instance, the threshold test described below (25% voting rights) is generally waived for EU/EEA investors with cooperative tax treaties. However, any non-French investor (including EU) is subject to screening if acquiring control of sensitive activities.

- French Target Criterion: The target must be a French entity (or business) – either a company incorporated in France or a branch of a foreign company located in France. In practice, acquiring a French company qualifies. If a foreign group is buying assets (and not a French entity per se), note that acquiring “all or part of a business line” of a French company can also trigger FDI review if that business line involves sensitive activities.

- Sensitive Activities Criterion: The target company must engage in certain protected sectors or activities deemed sensitive to public order, public security, or national defense. These sectors are defined in an exhaustive list in Article R.151-3. They include traditional strategic industries (defense, arms and munitions, intelligence, encryption, etc.), as well as critical infrastructure and technologies. Over the years, France has expanded this list to cover a wide array of areas: energy supply, water, transportation, telecommunications, public health, data centers, artificial intelligence, semiconductors, cybersecurity, robotics, space/aeronautics, critical raw materials and even certain food security and healthcare-related industries. For example, a logistics company might be subject if it operates critical transport infrastructure; a company with extensive personal data handling might fall under strategic technology. In the context of real estate, owning land itself is not a sensitive activity – unless the real estate is strategically located (e.g. near a military base or critical facility) or the company’s use of it qualifies (e.g. operating a vital logistics hub for defense supplies). Generally, it’s the business conducted on the site or the services provided that matter for FDI, rather than property ownership.

Two types of trigger thresholds are considered for covered investments:

- Acquiring Control: If the foreign investor will acquire control of the French company (defined similarly to corporate law control, e.g. >50% voting rights or de facto control), or if they acquire all or part of a sensitive business line, prior authorization is required (for any foreign investor, including EU).

- Minority Investment Threshold: Additionally, for non-EU/EEA investors, crossing 25% of voting rights in a French sensitive company also triggers the need for approval. As a temporary COVID-era measure, France had lowered this threshold to 10% for acquisitions of listed French companies; as of 1 January 2024, that 10% threshold for listed targets by non-EU investors is now permanent. (This means a non-EU acquirer of even 10% of a Paris-listed company in a sensitive sector must file for approval.) Investors from the EU/EEA are exempt from the 25%/10% threshold rule, but again, if they acquire control, they are caught just like others.

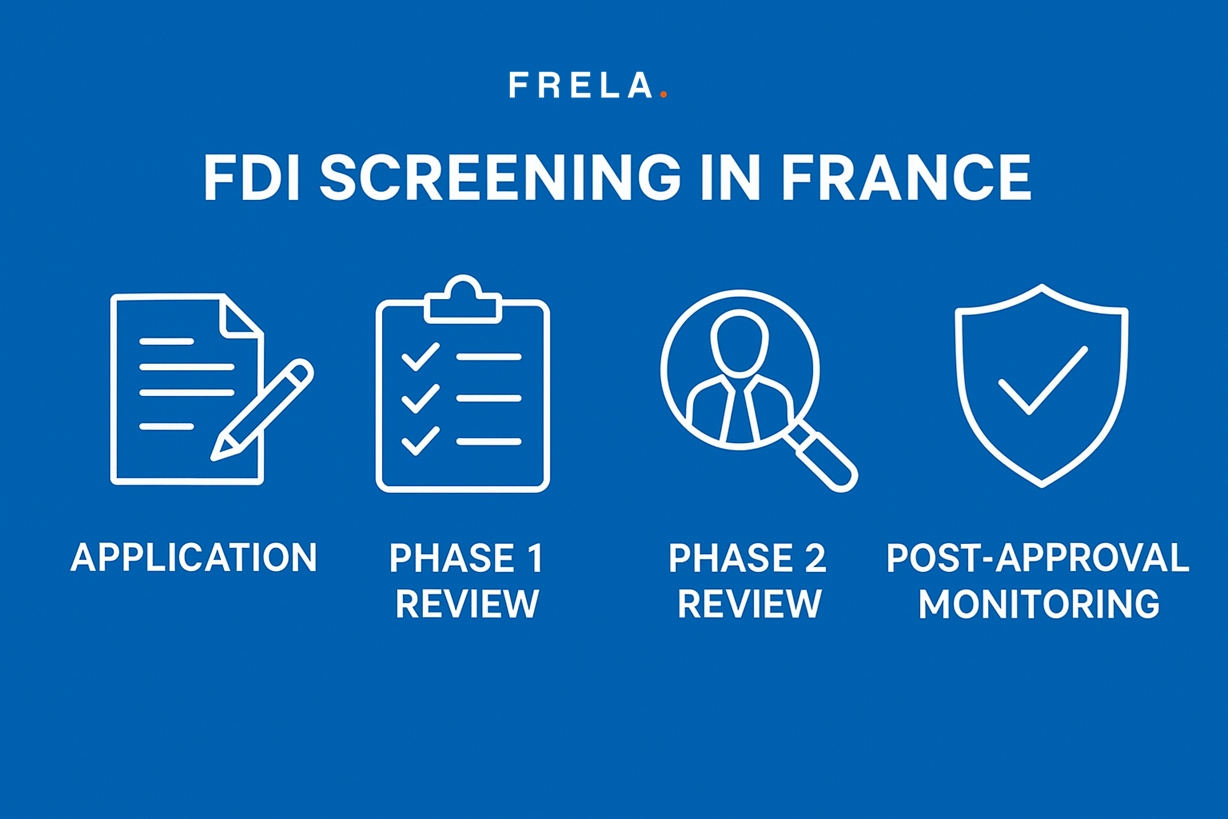

For a foreign group planning to acquire a French company with significant real estate, the key is to assess if the target’s activities fall under FDI scrutiny. If yes, the transaction timeline needs to accommodate the approval process. The procedure works as follows:

- Application: The investor (or investor together with the target) submits an application to the Ministry of Economy (typically to the Treasury Department’s dedicated unit). The application details the investor’s profile, the target’s business, the proposed deal, and addresses why it might be sensitive.

- Phase 1 Review (30 business days): The Ministry has 30 working days from receiving a complete filing to decide whether: (a) the investment is outside the scope (no approval needed), or (b) it is approved outright, or (c) a deeper review (Phase 2) is required. In many cases, straightforward investments receive clearance in this first phase, sometimes with a simple acknowledgement letter if no authorization was actually required.

- Phase 2 Review (additional 45 business days): If the deal raises more significant national interest questions, Phase 2 is triggered. The Ministry then has up to 45 more working days to conduct an in-depth review. During this phase, the authorities often engage with the investor to discuss mitigation measures or conditions to secure approval. The outcome is either an approval (possibly with binding conditions to ensure national security interests are protected), or a refusal in rare cases. Conditions might include things like commitments to keep certain activities in France, security protocols for sensitive data, or even divestment of a part of the business not to be acquired.

- Post-Approval Monitoring: If conditions are imposed, the investor will be subject to compliance monitoring. Non-compliance or proceeding without approval can lead to heavy penalties, including fines and orders to unwind the transaction.

From a transaction planning perspective, if FDI approval is required, it must be made a condition precedent in the acquisition agreement. The parties should factor in the review timeline (up to ~75 business days, ~15 weeks in worst case) before closing can occur. It’s advisable to engage with French counsel early to determine if a filing is needed and to prepare the notification. In some cases, the investor can seek an informal opinion from the Ministry ahead of signing, to confirm whether the target’s activities are in scope – this can de-risk the timeline uncertainty.

France’s FDI regime has become more encompassing in recent years, reflecting a broader EU trend of screening foreign investments. However, for most acquisitions not touching critical defense or technology, approvals are typically granted without issue (sometimes with moderate conditions). Knowing the rules and preparing a strong application is key to avoiding delays.

About the Author :

Business lawyers, bilingual, specialized in acquisition law; Benoit Lafourcade is co-founder of Delcade lawyers & solicitors and founder of FRELA; registered as agents in personal and professional real estate transactions. Member of AAMTI (main association of French lawyers and agents).

FRELA : French Real Estate Lawyer Agency, specializing in acquisition law to secure real estate and business transactions in France.

Paris, 15 rue Saussier-Leroy, Paris

Bordeaux, 24 Rue du manège, 33000 Bordeaux

Lille, 40 Theater Square, 59800 Lille

This article is provided for general information only and may not reflect the most recent legal or tax developments. It does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us for personalised guidance before making any decision.