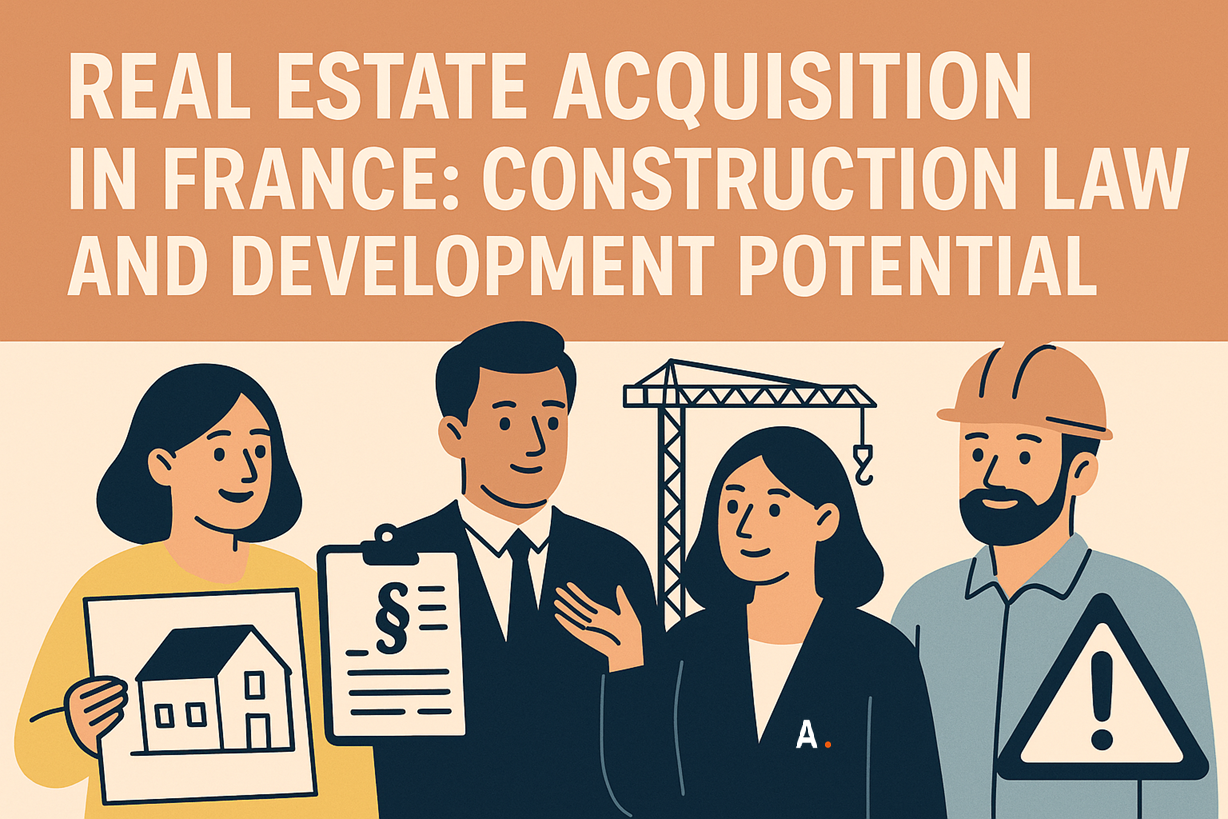

Real estate acquisition in France: construction law and development potential

Buying a property is only the first step; many investors, individuals or companies, then consider renovating, expanding or building in order to increase the value of the property or make the most of it. Construction law in France also has specificities to be aware of, otherwise your project will be delayed or even stopped by the administration or neighbors.

Building permits and permits required.

As mentioned in the Urban Planning section, most major works require a prior building permit. This concerns the construction of a new building, but also extensions of more than 20 m² (or more than 40 m² in urban areas covered by a PLU, the threshold beyond which a permit is required if the total surface area exceeds 150 m²). More modest works (extension from 5 to 20 m², modification of the façade, division of land) must generally be the subject of a prior declaration of works, a simplified but also mandatory procedure. A foreigner who buys a house with the intention of converting the attic or adding an outbuilding should be aware that the lack of prior authorisation makes the work illegal, with the risk of a demolition order or a fine in the event of an inspection. It is therefore necessary to submit a file to the town hall and obtain the authorization order before starting the work. The processing times, from 1 to 3 months depending on the case, must be integrated into the project schedule. In addition, after obtaining the permit, there is an incompressible period of 2 months for third party appeals during which the permit posted on the land can be contested by the neighbors or by the maf.fr prefecture. This point often surprises foreign project owners: even with a valid permit, a neighbour who is unhappy with the height of the future construction, for example, can file a non-contentious or contentious appeal to try to have the permit cancelled. In concrete terms, a foreign investor who has obtained a permit to raise his building could see a neighbour refer the matter to the administrative court within 2 months, which would suspend the construction site for the duration of the judgment. It is therefore prudent, when buying a property with a work project, to take into account these deadlines and legal hazards.

Professionals and technical compliance.

France requires the use of certified professionals at certain stages. In particular, if the construction or extension project brings the total surface area to more than 150 m², the use of a qualified architect is mandatory to draw up the architectural project (plan and permit file). Many foreigners do not expect this legal requirement to hire an architect (they sometimes think they can design themselves or via a builder), but the Urban Planning Code imposes it in order to guarantee the quality of the constructions. In addition, all construction must comply with the Construction and Housing Code – a set of technical standards (solid foundations, seismic standards, thermal and acoustic insulation, disabled accessibility for public buildings, etc.). Unfamiliar project owners must be assisted by a competent project manager. Once the work is completed, a declaration of completion and conformity of the work will have to be submitted to the town hall. The town hall can check within 3 months that the construction complies with the permit granted. If any significant deviations are observed (surface area exceeded, height not respected, etc.), the owner is exposed to sanctions and the obligation to comply. We can thus see that the entire construction cycle in France is monitored by the administration to ensure compliance with urban planning and technical rules.

Prior legal audit and easements.

Before launching a construction project on an acquired property, a wise investor will carry out a legal audit of the site. This consists of verifying the existence of easements that may affect the development potential: easement of passage for the benefit of a neighbour (which would prevent the fence from being completely fenced), easement of view limiting possible openings, easement of public utility (for example an underground pipe, or the classification as a Natura 2000 reserve prohibiting certain constructions). The notary has normally reported these easements at the time of purchase, but it is important to measure the concrete impact on the planned work. Similarly, an audit will look at the building’s history : if it has been altered without a permit in the past, the buyer potentially inherits an offence that has already been committed. For example, a previous owner was able to convert a garage into a studio without authorization or tax declaration: this irregular situation could be criticized during future works or an urban planning control. It is therefore advisable to regularise the situation (by filing a regularisation permit, if possible) before proceeding. This audit can be carried out by a real estate lawyer or a specialized design office, in order to secure the project.

Case in point: a Swiss investor buys a former postal inn classified as a historical monument, with the intention of renovating it into a hotel. The legal audit revealed several constraints: a non-building easement on the courtyard (requested by the State at the time of the classification) preventing any modern extension, the obligation to use traditional materials validated by the Architect of the Buildings of France, and the need for a special authorization for heritage sites in addition to the building permit. Thanks to this audit, the investor adjusts his project and his budget (the work will have to be done by “Historic Monuments” approved craftsmen, which are more expensive). Without this preliminary study, he could have embarked on an unfeasible or risky project.

Compliance and Responsibilities.

Once the project has been completed, the foreign investor who has become the project owner must know that in France, the liability of builders is governed by law. Any company that has carried out work is subject to a ten-year guarantee on major works: for 10 years, in the event of a defect compromising the solidity or the purpose of the work, the owner can turn against it. In practice, it is essential to choose companies insured for ten-year liability and to take out construction damage insurance yourself before the start of the work (mandatory for any private project owner, although still too often ignored). This insurance allows, in the event of a claim, to be compensated quickly for repairs without waiting for court decisions. A foreign investor who builds a villa to resell it will need this insurance, as the subsequent buyer will ask for it to be covered for potential defects. These guarantee mechanisms are an asset of the French system, but need to be put in place from the start of the project.

In summary

Carrying out a construction or renovation in France is a very legally regulated process, from the initial authorisation to the compliant delivery of the work. The specificities to be remembered for a foreigner are: the obligation to go through administrative procedures (permits, declarations) before the work, the possibility of additional delays (third-party appeals, consultations with architects of historic monuments, etc.), the obligatory use of certain professionals (architect above a threshold, insured companies), and the existence of strong legal guarantees (ten-year guarantee, damage to the work). With good preparation and by surrounding yourself with competent professionals, it is quite possible to carry out a construction project in France, but you must devote time to it and arm yourself with administrative patience. The key word is compliance: any initiative that does not comply with the rules may be called into question sooner or later.

In conclusion, acquiring a property in France as a foreigner is an accessible and safe project, provided that you master the legal context. The French legal framework offers a high level of protection (notaries, withdrawal periods, etc.) while including specific constraints that it would be unwise to ignore (meticulous urban planning, complex taxation, construction formalities). In summary, an international investor will need to:

- Understand the role of the notary and respect the contractual stages (from the preliminary agreement to the authentic deed);

- Find out about urban zoning and any restrictions (never assume that you will be able to build or transform without verification);

- Plan the taxation of your investment (purchase costs, annual taxes, rental income regime, capital gains, inheritance) and choose the appropriate legal vehicle (direct or SCI) according to your situation;

- Anticipate the construction process and surround yourself with professionals to remain legal and compliant.

Thanks to such preparation and the advice of experts (lawyers, notaries, tax specialists, architects), foreign individuals and companies will be able to invest in France with peace of mind and take full advantage of the advantages of the French real estate market, without any unpleasant legal surprises. French law, which is sometimes confusing, offers a robust framework guaranteeing the security of transactions and the sustainability of investments – which, in the end, also reassures informed international investors.

About the Author :

Business lawyers, bilingual, specialized in acquisition law; Benoit Lafourcade is co-founder of Delcade lawyers & solicitors and founder of FRELA; registered as agents in personal and professional real estate transactions. Member of AAMTI (main association of French lawyers and agents).

FRELA : French Real Estate Lawyer Agency, specializing in acquisition law to secure real estate and business transactions in France.

Paris, 15 rue Saussier-Leroy, Paris

Bordeaux, 24 Rue du manège, 33000 Bordeaux

Lille, 40 Theater Square, 59800 Lille

This article is provided for general information only and may not reflect the most recent legal or tax developments. It does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us for personalised guidance before making any decision.