Legal strategies for tax optimization before the sale

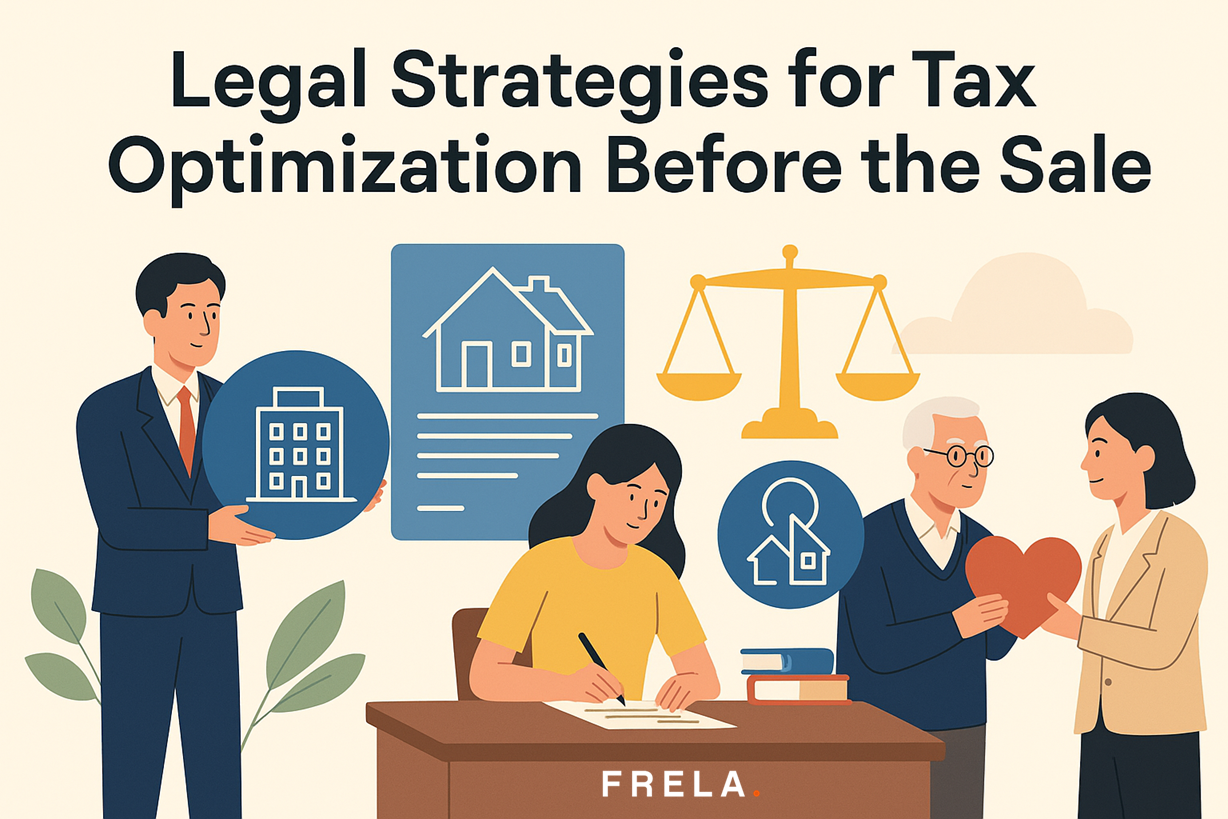

Faced with the taxation of capital gains and social security contributions, a non-resident seller can consider certain strategies before the sale to legally optimise the tax burden. It is essential to stay within the legal framework (no fraud or undervaluation of the sale price, which would be very risky). Here we discuss several well-known asset optimisation levers: holding via a real estate company (SCI), donating the property before sale, and dismembering ownership. Each of these arrangements has specific legal and tax implications, which should be reviewed with professional advice to verify their suitability on a case-by-case basis.

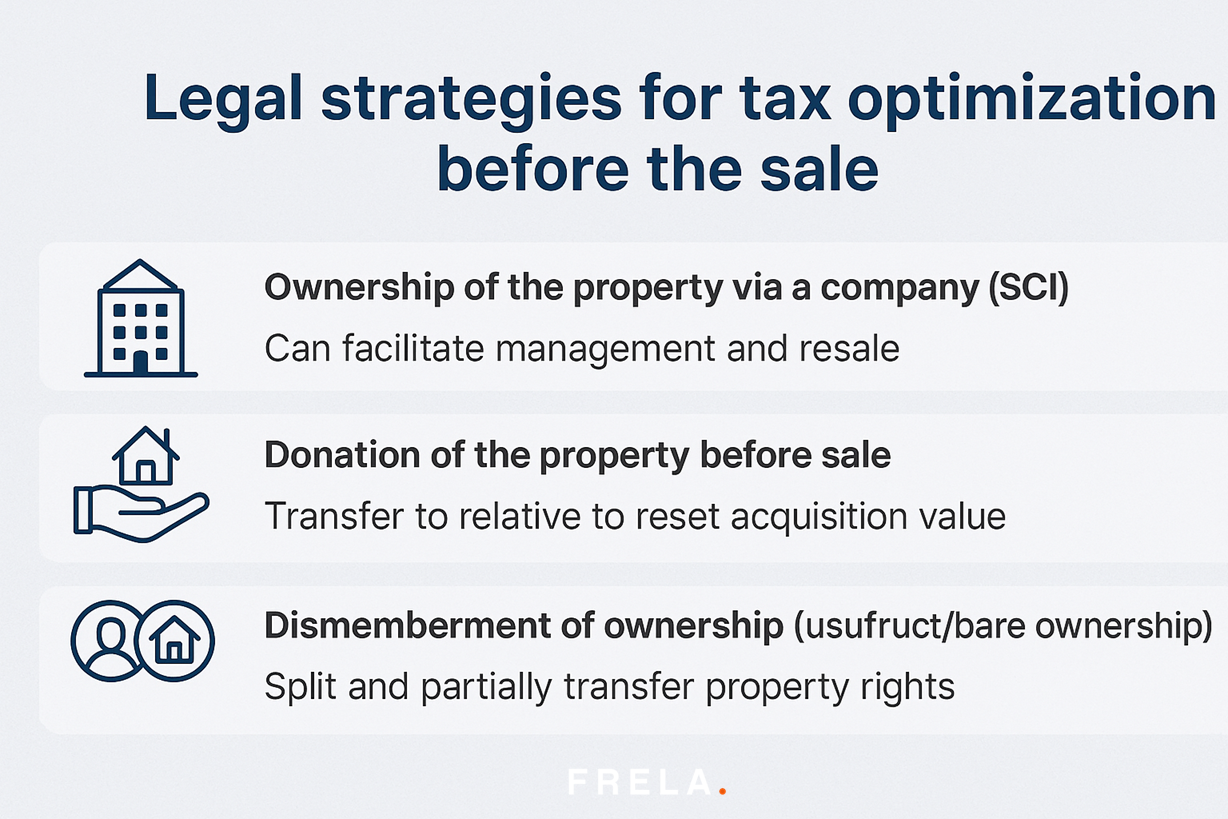

Ownership of the property via a company (SCI):

Many foreign investors choose to acquire and hold their French property via a Société Civile Immobilière (SCI). In terms of sale, selling the property from an SCI can have several indirect advantages. Firstly, if several people or members of a family own a property together, the SCI facilitates the management and resale (it is simpler to transfer shares or organise the transfer to the heirs). In terms of capital gains tax, a transparent SCI (subject to income tax) does not provide an immediate tax advantage: the capital gain is calculated and taxed as if the partners were selling directly, at a rate of 19% (if partners are natural persons) and with the same allowances for the duration of the company. The fact of being a non-resident does not worsen the rate thanks to the alignment made in 2015. In other words, there is no overtaxation solely because of the SCI or the foreign status. On the other hand, holding via an SCI can allow you to choose to be subject to corporate income tax (CIT), if you are an option. In this case, the capital gains regime is that of professionals: there is no longer an allowance for duration, but the capital gain (or the result of disposal) is subject to corporate income tax at the rate of 25% (in 2025) on the net accounting capital gain. This option is generally only interesting in specific schemes, because at the CIT the taxable base can be increased by the depreciation applied to the property and the taxation does not disappear over time (unlike the exemption after 22/30 years for individuals). Nevertheless, a company with corporate income tax could allow the proceeds of the sale to be reinvested in another real estate project by avoiding immediate taxation at the personal level (the company keeps the net corporate income tax funds, and the partner will only be taxed if he distributes a dividend or in the event of a withdrawal of funds). For a non-resident investor who plans to pass on the property to his or her children, the SCI also offers advantages: the possibility of gradually giving away shares (which can be tax-optimised thanks to the allowances on gifts every 15 years, by splitting the value). In short, the primary purpose of creating an SCI is not to reduce the tax on the capital gain of the sale, but it is a legal tool that facilitates management and transmission. From a purely tax point of view on the sale, it should be noted that an SCI not subject to corporate income tax does not penalise the non-resident seller (taxation at 19% identical to a direct holding), while an SCI subject to corporate income tax may, in certain cases, allow a tax deferral strategy (at the cost of the loss of allowances for duration). Any decision to hold a company must be carefully considered with advice (notary or tax lawyer), depending on the value of the property, the time horizon of ownership and family objectives.

Donation of the property before sale:

The gift before sale is a classic strategy for “purging” the unrealised capital gain. It consists of the owner giving the property to a relative (usually an heir: child, grandchild, etc.) then that the beneficiary of the gift makes the sale to the final buyer. The tax advantage lies in the fact that the gift does not entail taxation on the capital gain (since there is no sale for consideration, the transfer is free of charge) and that the beneficiary (donee) will be deemed to have acquired the property at market value on the day of the gift. Thus, when the donee resells, the taxable capital gain will be calculated in relation to the value of the property at the time of the donation, and not in relation to the initial acquisition price of the donor. If the sale takes place shortly after the gift and at the same price as the value declared in the deed of gift, the capital gain will be very low or even zero, thus avoiding the 19% tax (+ social security contributions). Example: a non-resident bought an apartment for €200,000 20 years ago, he can sell it for €500,000 today (unrealised capital gain €300,000). If he sells directly, his taxable capital gain after allowances will still be significant (20 years of ownership ≈ 60% of income tax allowance, so taxation on ~€120,000, i.e. ~€23,000 of tax + 17.2% of PS on ~€210,000 remaining, etc.). If he decides instead to give the property to his two children before the sale, valuing it at €500,000 in the deed of gift (real market value), no capital gain is due by the father. The children become owners and can sell for €500,000 without capital gain (€500,000 – €500,000 base = 0). As a result, capital gains tax is saved. However, several precautions and costs must be considered:

-

- The gift itself can trigger gift tax if it exceeds the legal allowances (€100,000 per parent and per child every 15 years, for example). In our example, €500,000 to two children = €250,000 each, so after deduction of €100,000, there is still €150,000 taxable for each, resulting in about €30,000 in rights per child (on the scale of 2025). In total ~€60,000 in gift tax. Admittedly, this is less than the ~€23,000 in capital gains tax + ~€36,000 in PS that the father would have paid (total ~€59,000), but the saving is small here. If the property was held for a short time (i.e. a large taxable capital gain) and/or if the gift allowances are sufficient to cover the value, the operation is much more advantageous.

- The gift must not be made on the condition of resale or for the indirect benefit of the former owner, otherwise the tax authorities could reclassify the transaction as a taxable direct sale. This is called a “donation-transfer” arrangement. Legally, to be valid, the gift must be irrevocable and made before signing a commitment with a buyer. In practice, the risk of reclassification is eliminated if the gift is made without the property being under a firm promise of sale. Timing is crucial: for example, you can receive an offer to purchase, but it is better to sign the donation before concluding a sales agreement with the final buyer.

- The donor must accept that he or she will not receive the sale price directly: it is the children (donees) who will receive the proceeds of the sale, since they have become owners in the meantime. However, it is possible to optimize the use of these funds as a family (the children can help financially afterwards, but be careful not to violate the spirit of the donation).

- Despite these constraints, the gift before sale is a powerful and legal tool for tax optimization on capital gains, which is very popular in wealth planning. According to notaries, this is a “surprisingly effective strategy for purging latent capital gains” according to a report by the Congress of Notaries of France (2016). The key is to calculate the net gain, taking into account any gift tax and costs (deed of gift, etc.), and to check that it is consistent with the family objectives. For a non-resident, it will also be necessary to consider the tax law of his country of residence (some countries tax gifts received or have rules for remittance of funds after sale).

Dismemberment of ownership (usufruct/bare ownership):

Dismemberment consists of splitting full ownership into bare ownership (holding the substance of the property) and usufruct (right of use and to receive income). It is first and foremost a lever for estate optimisation (for example, giving the bare ownership of a property to one’s children while retaining the life usufruct makes it possible to reduce the taxable base of gifts and to transfer the property at a lower tax cost). Regarding the sale of a dismembered property, several strategies exist:

- If the non-resident seller dismembered the property before the sale (for example, he or she donated the bare ownership to his or her children a few years earlier, keeping the usufruct), the sale of the property requires the joint participation of the usufructuary and the bare owners. For tax purposes, the capital gain is calculated by dividing the sale price between the usufruct and the bare ownership, according to their respective value on the day of the sale, and comparing it with the acquisition values of each fraction. Each party (usufructuary and bare owner) is taxed on its share of the gain. The tax authorities consider that the purchase price of each right corresponds to the value that was used when the dismemberment was set up. Thus, if the usufruct has been retained by the parent (donor) and the bare ownership has been transferred, the values appearing in the deed of gift will be referred to to determine the taxable gain of each person. This can be complex, but often interesting: part of the overall capital gain may have already been purged at the time of the gift (as seen above) since the bare ownership transferred has a more recent base value. In addition, the starting point of the holding period is taken on the date of entry into possession of each right (e.g. the bare owner calculates his allowance for the period since the gift). This configuration, although advanced, shows that dismemberment and early donation can combine their effects to reduce taxation.

- A seller may also consider partially selling the property in dismemberment. For example, an elderly owner wishing to optimize can sell the bare ownership of the property to an investor, while retaining the life usufruct. He thus immediately obtains a sum of money (the price of the bare ownership, which is a fraction of the total price of the property according to his age: the younger he is, the more the bare ownership is worth, since the life usufruct has a lower value; at the age of 70 the usufruct is worth 30% of the property, so the bare ownership ≈70% of the total value). The taxable capital gain will then be calculated solely on the price of the bare ownership transferred, which is lower than the price of full ownership, which reduces the immediate tax by the same amount. The usufructuary will not be taxed on the operation (he has not sold anything). Upon his death, the usufruct will be extinguished and the bare owner will become the full owner without tax (the extinction of the usufruct is not a taxable event in itself). This arrangement is similar to a form of life annuity without annuity or dismemberment-transfer. Please note: it must be financially balanced (the price of the bare ownership must correspond to the tax scales or a realistic economic value) in order not to be reclassified. In addition, the seller definitively renounces any share of the property for his heirs, since the buyer will eventually recover full ownership. It is therefore a strategy with a rather patrimonial aim (ensuring capital during one’s lifetime) and fiscal (reducing the taxable base).

- Finally, it should be noted that if a property has been held in dismemberment (e.g. inheritance where the surviving spouse has the usufruct and the children the bare ownership, then they sell jointly), the notary will be able to apply the appropriate tax regime. This is not a priori optimization, but it is good to know that the law has provided for these cases to avoid double taxation.

Summary on tax optimization:

A non-resident has legal levers to reduce the tax on the sale, but each option must be handled with care. The SCI is above all a management and transmission tool, to be considered only if it brings a civil gain (it does not reduce the capital gain itself to the income tax, except for the choice of the corporate tax which has other counterparts). The gift before sale can drastically reduce or cancel the taxable capital gain by raising the acquisition value to the current value, possibly at the cost of gift tax and family planning. Dismemberment can be integrated into the strategy (transferring the bare ownership in advance, or selling only part of the rights) to fragment the tax base. These arrangements require expert advice (notary or tax lawyer) in order to measure all the legal, tax and financial effects, including with regard to the tax authorities of the country of residence. Anticipation is key: it is often too late to optimize when you are already engaged in sales, hence the importance of consulting a professional beforehand.

About the Author :

Business lawyers, bilingual, specialized in acquisition law; Benoit Lafourcade is co-founder of Delcade lawyers & solicitors and founder of FRELA; registered as agents in personal and professional real estate transactions. Member of AAMTI (main association of French lawyers and agents).

FRELA : French Real Estate Lawyer Agency, specializing in acquisition law to secure real estate and business transactions in France.

Paris, 15 rue Saussier-Leroy, Paris

Bordeaux, 24 Rue du manège, 33000 Bordeaux

Lille, 40 Theater Square, 59800 Lille

This article is provided for general information only and may not reflect the most recent legal or tax developments. It does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us for personalised guidance before making any decision.